Adapted from: Recording and Analysing Burial Grounds © Harold Mytum and the Council for British Archaeology, 2019, 2020, with further contributions from Harold Mytum, May 2020.

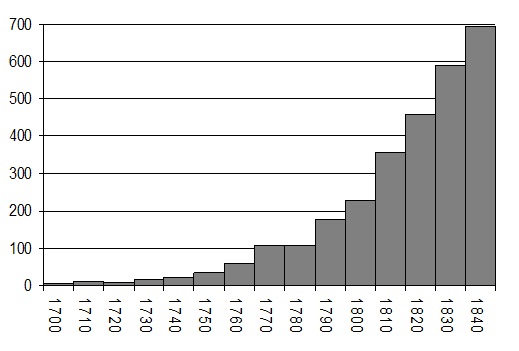

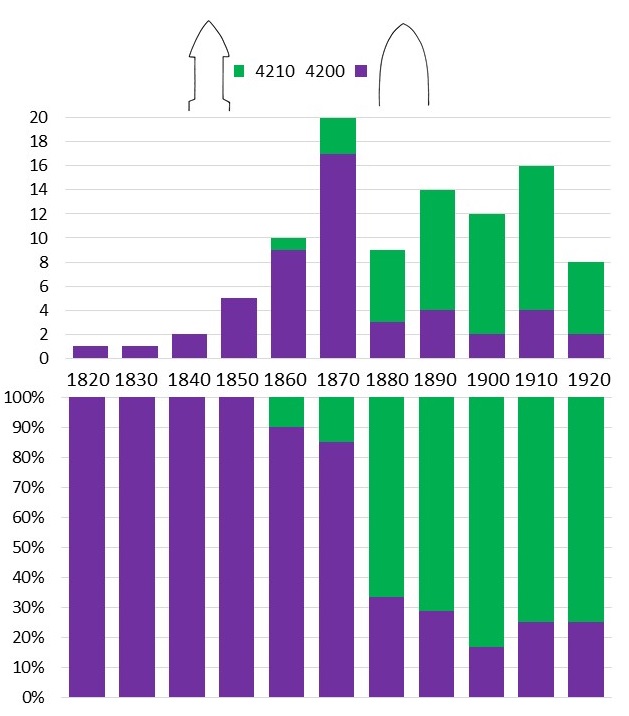

One of the easiest questions to ask and answer after doing a survey is when does commemoration start and how did it increase in popularity. Using the stones data set, it is possible to see the rise in memorials year by year, but often is better presented in a bar chart by decade.

You can look at the charts and consider when memorials start, when they become numerous, and any sharp changes in the pattern. Many burial grounds show a decline in memorials because other alternative locations – such as nonconformist burial grounds or cemeteries – may have opened in the area. There is also the rise of cremation and, although some cremations are marked, many are not or are never deposited in a formal burial ground.

You may have older sets of transcripts of inscriptions, and they may have evidence that is no longer surviving – inscriptions may have eroded and memorials may have been removed. That can provide its own perspective on the memorials that survive.

The graveyard boom in terms of monument erection has been written about by Sarah Tarlow and Harold Mytum.

Mytum, Harold 2006 ‘Popular attitudes to memory, the body, and social identity: the rise of external commemoration in Britain, Ireland, and New England’. Post-medieval Archaeology 40.1: 96-110.

Tarlow, Sarah 1998 ‘Romancing the stones: the graveyard boom of the later 18th century’. In M. Cox (ed.) Grave Concerns: Death and Burial in England 1700-1850: 33-43.

Tarlow, Sarah 1999 Bereavement and commemoration: An archaeology of mortality. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford.

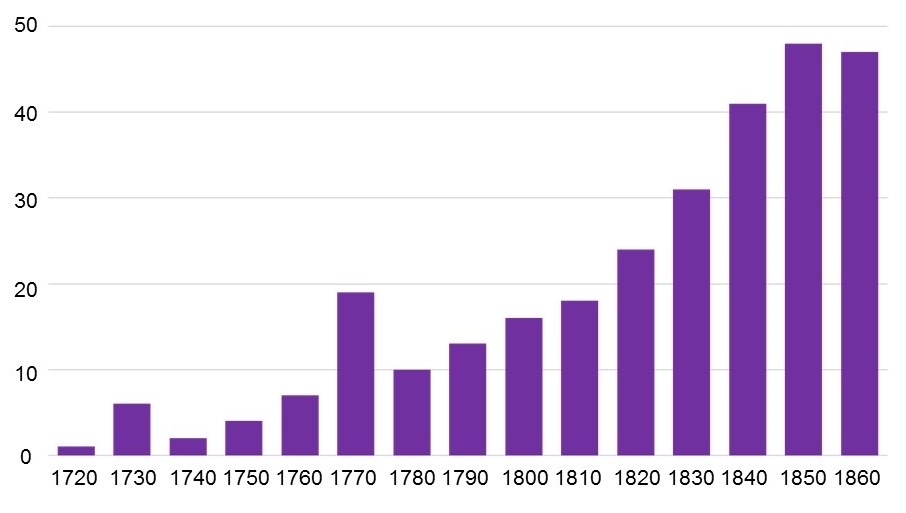

One of the questions that you might like to investigate is how many people were commemorated out of those who were buried. This involves collecting data from the burial register as well as from the graveyard. When collecting the register data, you have to decide whether you are just counting by year, say, or whether you wish to count men and women separately, or even explore the ages of the deceased. It depends on whether you wish to explore which sections of the population by age and sex tended to be remembered in the graveyard, or just the overall percentage as shown here.

The rate of representation seems to be very carried across the country, though so far very few studies have been completed and disseminated, so we at present have not clear explanation. The Pembrokeshire data suggests a high representation, that from Leicestershire shows a much lower rate. What does your graveyard show, and why might that be?

The representation issue has been discussed in these publications:

Mytum, Harold 2006 ‘Comparison of Nineteenth and Twentieth century Anglican and Nonconformist Memorials in North Pembrokeshire’. The Archaeological Journal 159, 194-241.

University of Leicester Graveyards Group 2012 ‘Frail memories: is the commemorated population representative of the buried population?’. Post-Medieval Archaeology 46.1: 166-195.

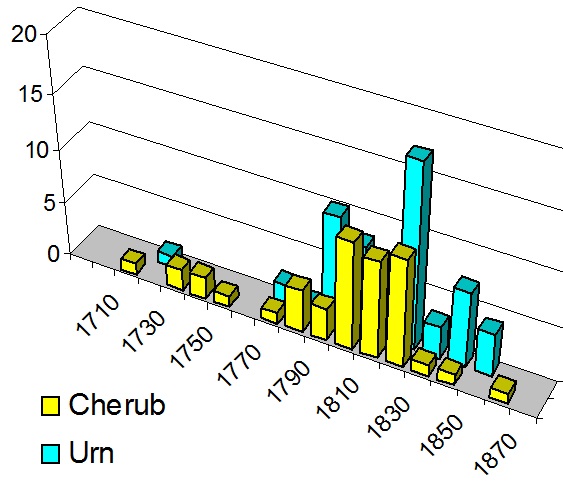

Memorials have symbols which are often carved in a local distinctive styles but which are in essence similar to those found elsewhere. You can investigate what symbols or motifs were popular – and when – from your data.

In this sample (derived from surveys in Pembrokeshire and Yorkshire) cherubs are regularly present in small numbers earlier than urns are popular, they overlap and then urns continue to be frequent after cherubs decline in use.

One graveyard may produce enough for such a graph – it depends on how many of your memorials are decorated. In some regions the popularity for cherubs is largely or even completely over before stone memorials start being erected. In other regions there are numerous cherub stones. You may have such memorials present but the date is unknown because of eroded inscriptions, but you may at a later stage of research have some idea of their date from the style of the carving using evidence from those that are dated.

There have been surprisingly few substantial studies of symbol popularity through time in Britain and Ireland, but there are classic examples from New England of the changes from death’s heads, cherubs and urns and willows. We also have early mortality symbols (but more varied), then cherubs, and the urns only sometimes with willow.

Dethlefsen, Edwin, and James Deetz. 1966 ‘Death's heads, cherubs, and willow trees: Experimental archaeology in colonial cemeteries.’ American Antiquity 31.4: 502-510.

Mytum, Harold 2006 ‘Comparison of Nineteenth and Twentieth century Anglican and Nonconformist Memorials in North Pembrokeshire’. The Archaeological Journal 159, 194-241.

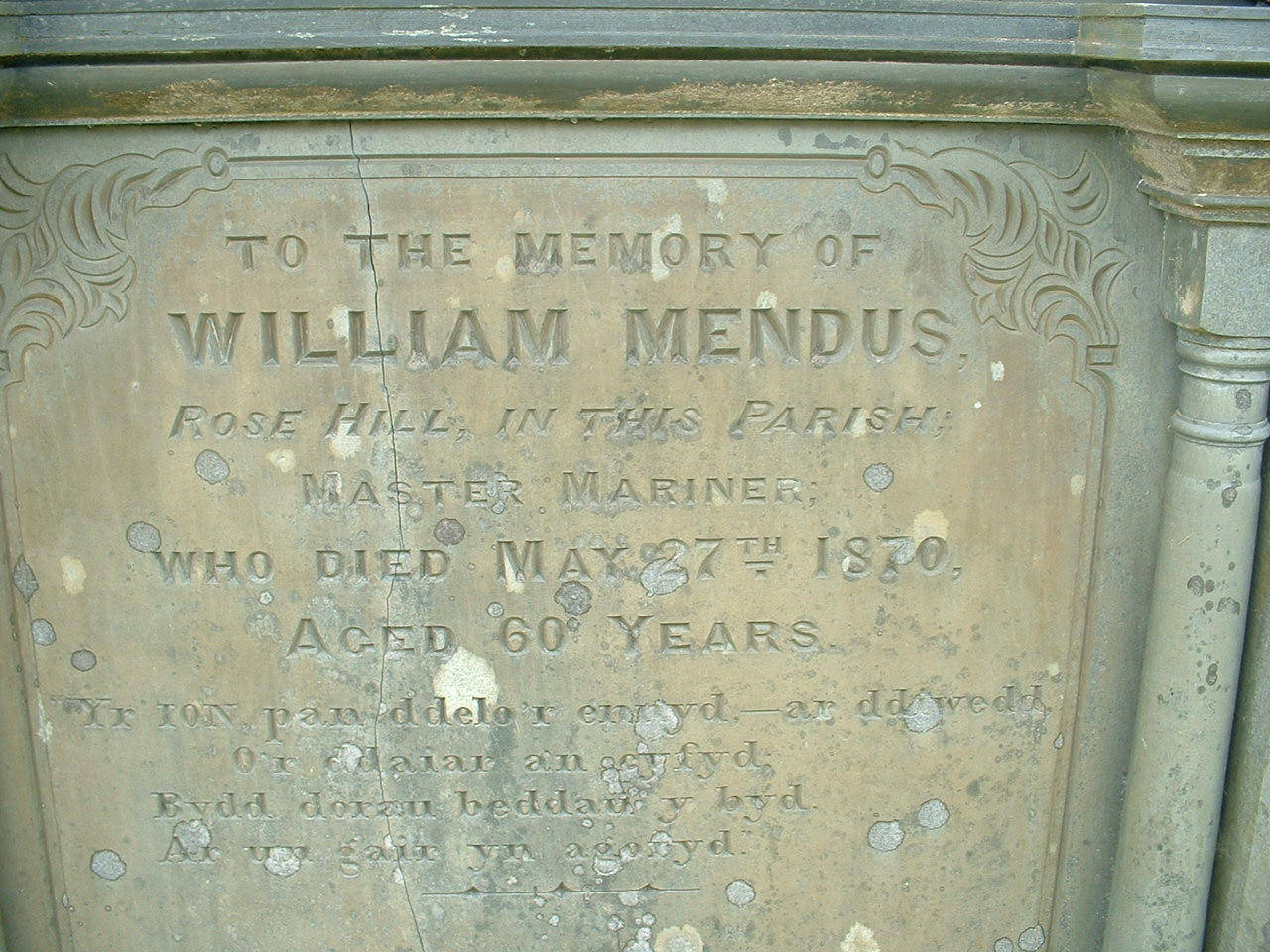

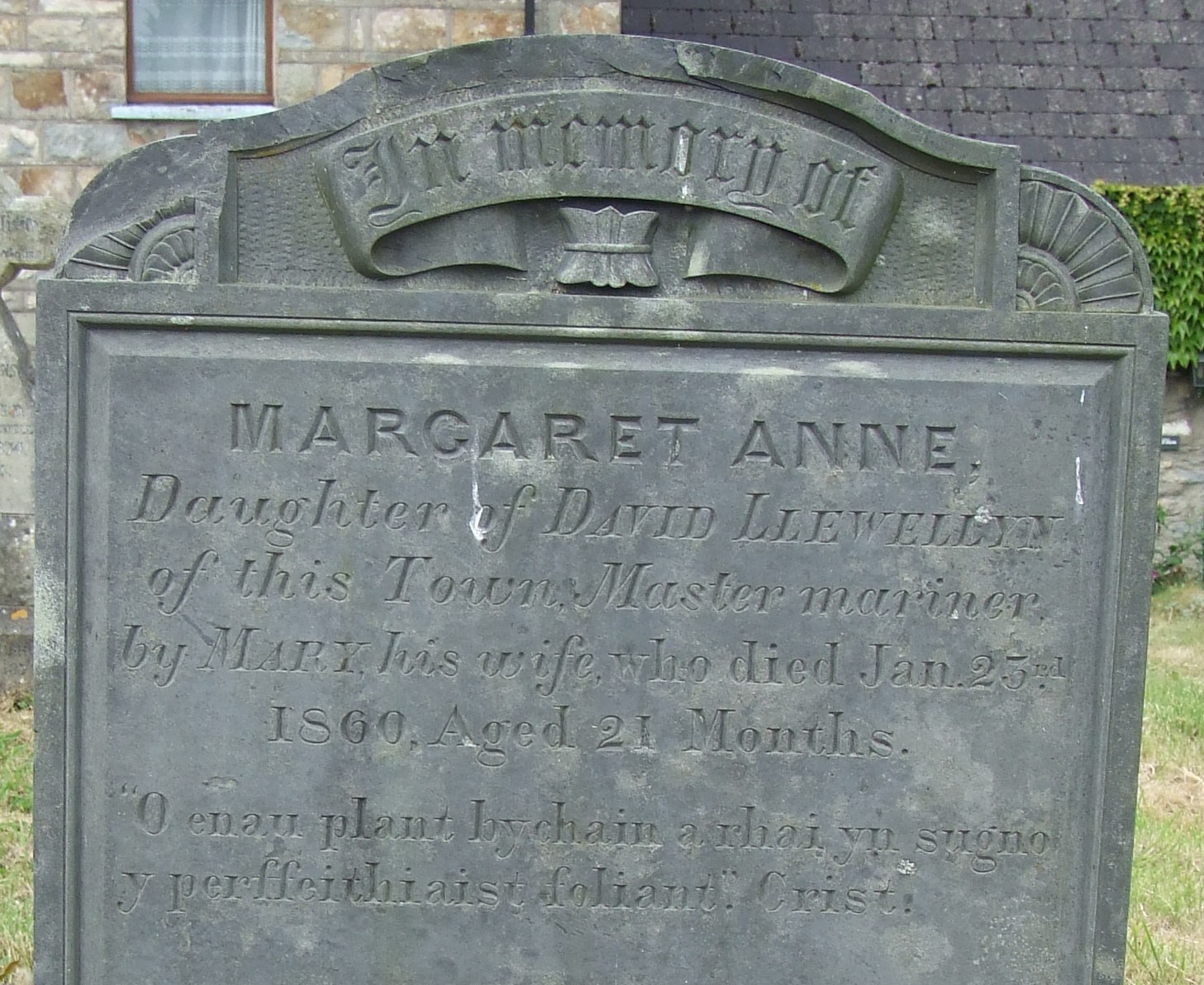

The inscriptions on memorials may indicate the occupation of the deceased, or sometimes of a relative such as of a parent when the burial is of a child. In some parts of the country many of the monuments mention occupations, in many others it is rare. If the profession comes with a title, for example an army rank such as Major, this gives an indication, but some such as Captain could refer to the army, or a nautical role.

The most consistent occupation that can be found is that of religious figures, normally parish priests but also more senior figures, or their relatives where their role is stated. Even in Anglican churchyards there are often memorials to nonconformist ministers as they were buried in the parochial graveyards when the chapel did not have its own burial ground. They are often also orientated at 180 degrees to other burials as, at the Second Coming, they will arise facing their congregation to lead them to the Promised Land.

Anglican and Roman Catholic clergy often have memorials which, in both form and symbolism, are distinctive. Usually a chalice and sometimes the bread of the host is depicted, and Gothic revival monuments are also more popular, though many other designs are also used.

Another profession which is often mentioned specifically is that of mariners, often because of their affluence Master Mariners, but others are also defined by their occupation. In such communities, other posts related to the sea such as harbour masters and customs officers are also often mentioned.

Mariners’ monuments have had the most attention.

Mytum, Harold 2006 ‘Popular attitudes to memory, the body, and social identity: the rise of external commemoration in Britain, Ireland, and New England’. Post-medieval Archaeology 40.1: 96-110.

Tarlow, Sarah 1998 ‘Romancing the stones: the graveyard boom of the later 18th century’. In M. Cox (ed.) Grave Concerns: Death and Burial in England 1700-1850: 33-43.

Tarlow, Sarah 1999 Bereavement and commemoration: An archaeology of mortality. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford.

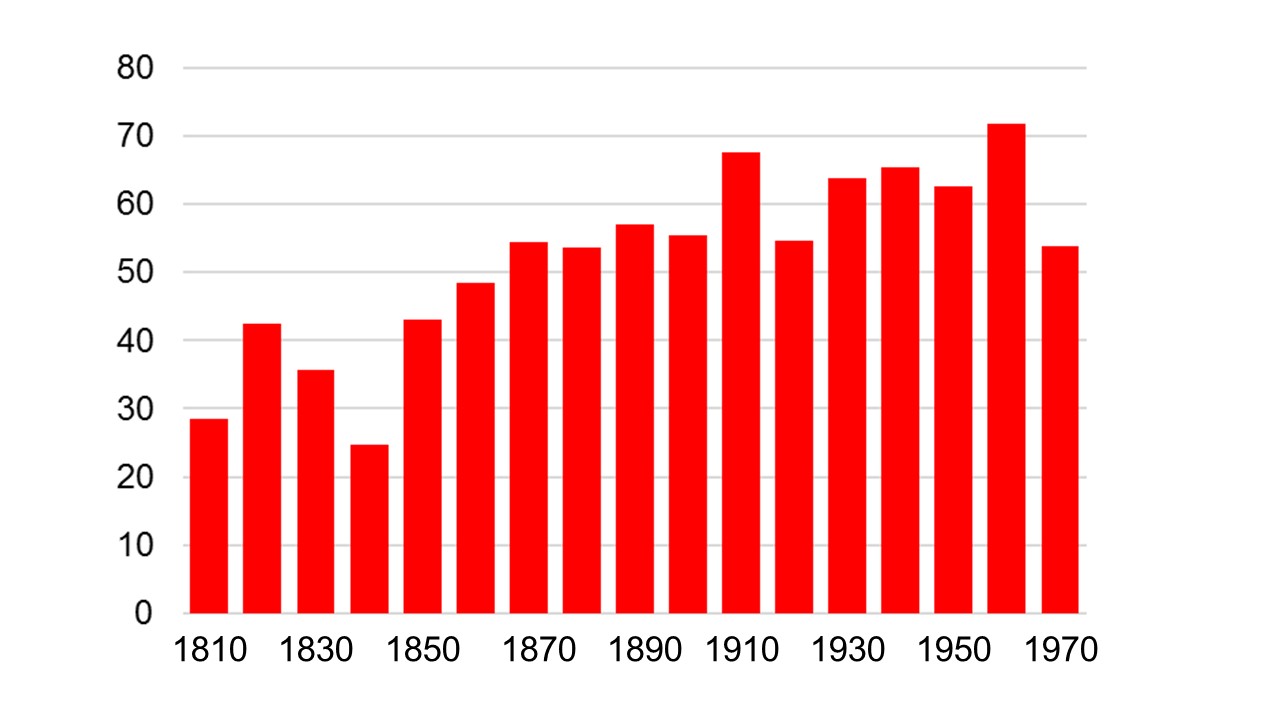

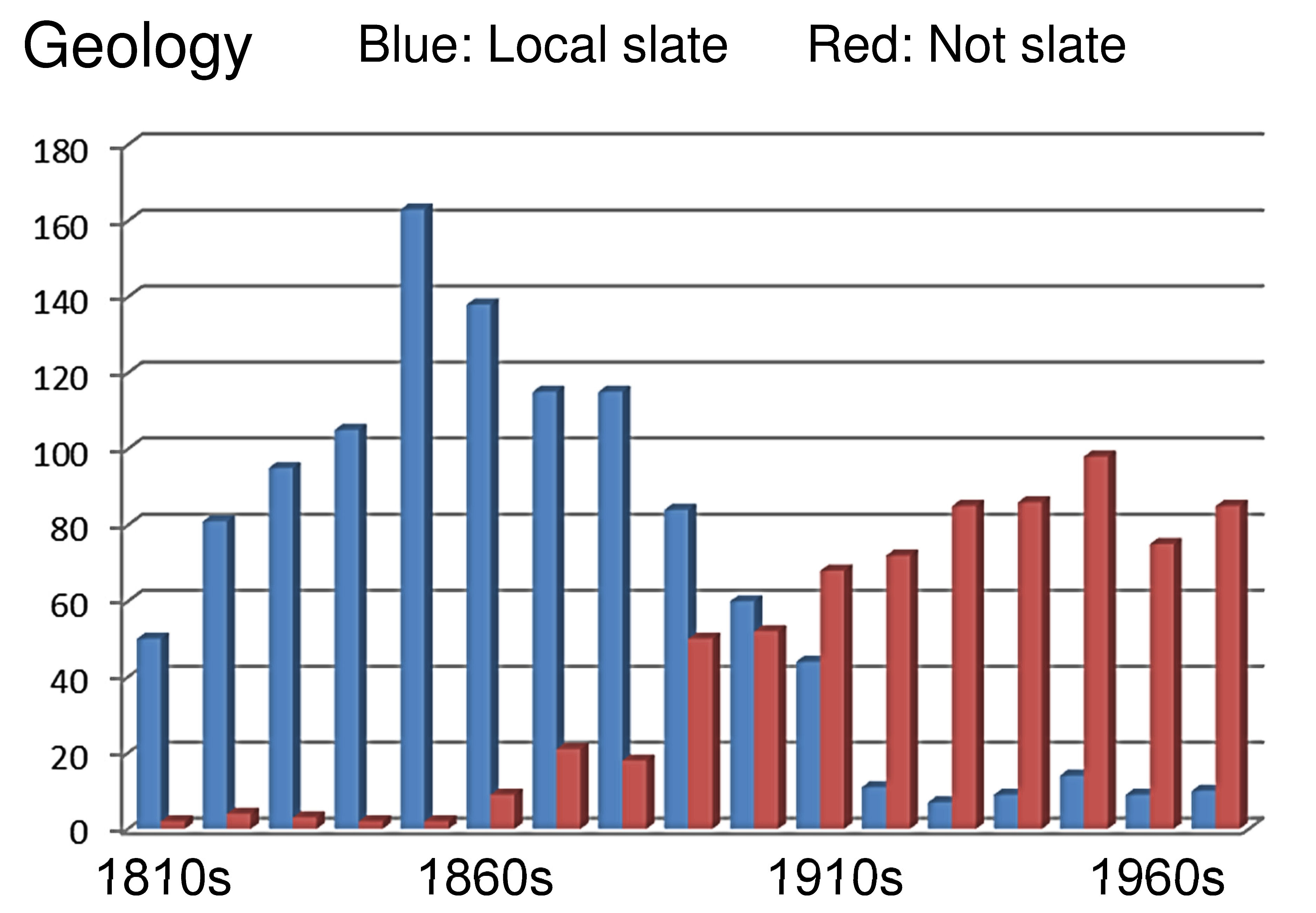

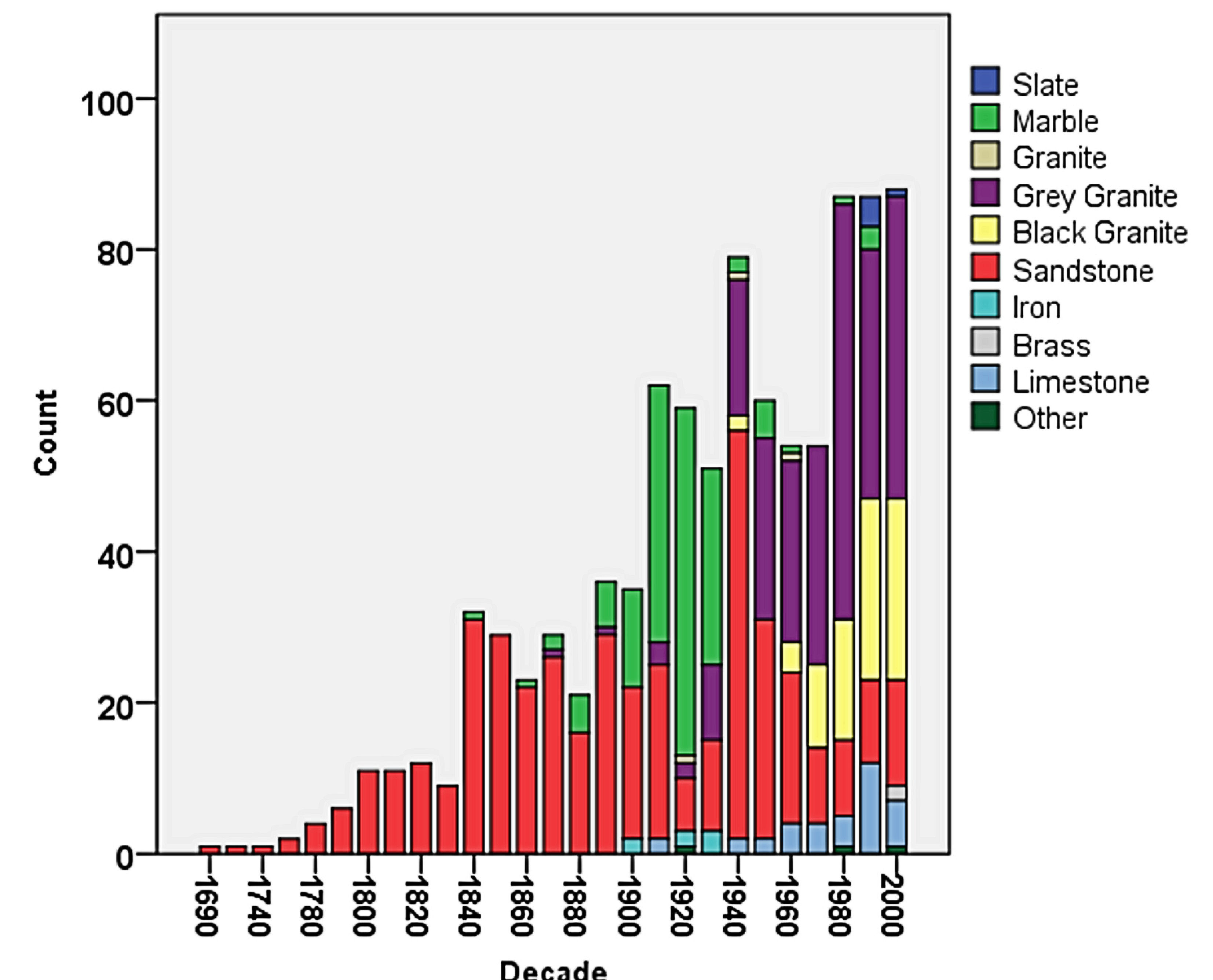

One of the things that can be most difficult is sorting out the geology of memorials, but the broad types are relatively easy. The main difficulty is to identify many of the marble monuments that have become discoloured, so their original white colour cannot now be seen. You can see to what extent your burial ground fits the national pattern. There may well be regional and local variations – for example, north Pembrokeshire with its excellent slate for headstones kept using local stone longer than some other areas.

Whatever your local preferred rock type for memorials – especially headstones – should be the dominant early choice for material, then gradually others were added to the repertoire. Often Marble appears next, but then granites become more common. In the early part of the 20th century there may be few local materials used at all.

The geology of the stones – and the use of other materials such as ceramics or cast iron – can tell us about communication and supply availability, but also about colour choices – white marble, pink, grey or black granite.

Materials also correlate strongly with certain memorial types (many crosses with stepped bases were marble), but that is another story …

Materials are been discussed in this publication:

Mytum, Harold 2006 ‘Comparison of Nineteenth and Twentieth century Anglican and Nonconformist Memorials in North Pembrokeshire’. The Archaeological Journal 159, 194-241.

There are also guides to geology in graveyards and cemeteries. We have supplied one here, as the coded classification is quite broad and does not cover many of the recent imported materials.

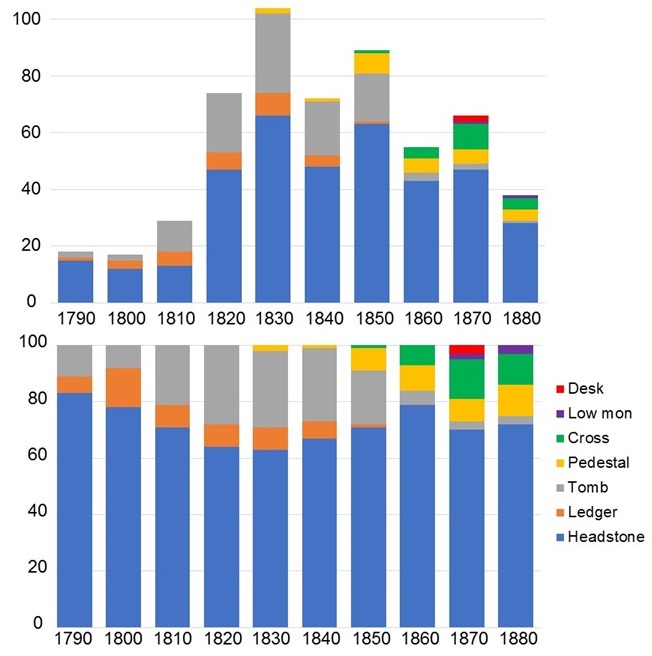

Memorials are often carved in a local distinctive styles which can be analysed closely from the photographs but still sit within broad traditions which are widespread. At one level there are similarities across the English-speaking world, but there are distinctive differences in emphasis and popularity in large regions of Britain and Ireland. You can investigate what monument forms were popular – and when – from your data; the larger your data set the more detailed your classifications can be. With many burial grounds a broad set of categories are the best starting point.

As the numbers per decade vary so much, it can be enlightening to also see a graph where each column represents all the memorials of that decade by percentage of type, so each bar is the same height. Then the proportions of each type is even clearer, even though some samples are quite small, so they are less reliable. Here, it is notable how many tombs – mainly chest tombs – were erected at this site in the early 19th century. Some of the forms that became popular in the city in the 20th century are just beginning to appear in the last decades shown here.

There have been surprisingly few substantial studies of the widespread monument categories or more detailed types that were found nationally (though some Regional styles have been discussed). The best discussion of them in a general way is still in F. Burgess (1963) English Churchyard Memorials, also republished in 2004 and is in print.

Memorial forms that occur frequently at a site (or several sites when the data sets are combined) can be looked at on their own, and their popularity assessed. For example, a simple pointed Gothic headstone 4200 and the same shape with indents on the sides 4210. The former tend to be carved in the popular local stone, the latter may also be made from the same source, but also is often found in white marble and granites of various colours.

These forms represent the least elaborate of memorials within the Gothic revival tradition that was popular in many Victorian and Edwardian buildings, and they are the simplest examples of what architectural and art historians have called the ‘battle of the revival styles.’ Others include the Classical, Egyptian and Romanesque revivals, all well represented in church and cemetery architecture and memorials. Some more complex monuments may contain elements from more than one style, sometimes in idiosyncratic combinations.

In this sample from Kirkdale, North Yorkshire, two shapes of Gothic headstones have been plotted and this shows clearly how the plain shape was popular first, and then examples with indented sides became popular and lasted much longer.

There have been surprisingly few substantial studies of monument types through time in Britain and Ireland; it is largely taken for granted but deserves much more local and regional study. Even the simple pattern seen above has not been reported in an academic publication.

The inscriptions on memorials provide names, dates and sometimes relationships which have long been appreciated by genealogist, but the texts give more social and cultural information than this.

The most obvious cultural indicator on memorials is the language used; for example, in Wales the choices between English and Welsh can be telling – and many stones reveal both languages, sometimes used for particular parts of the text. Some educated figures in the 18th and 19th centuries included Latin epitaphs. Immigrant groups may retain their language on monuments.

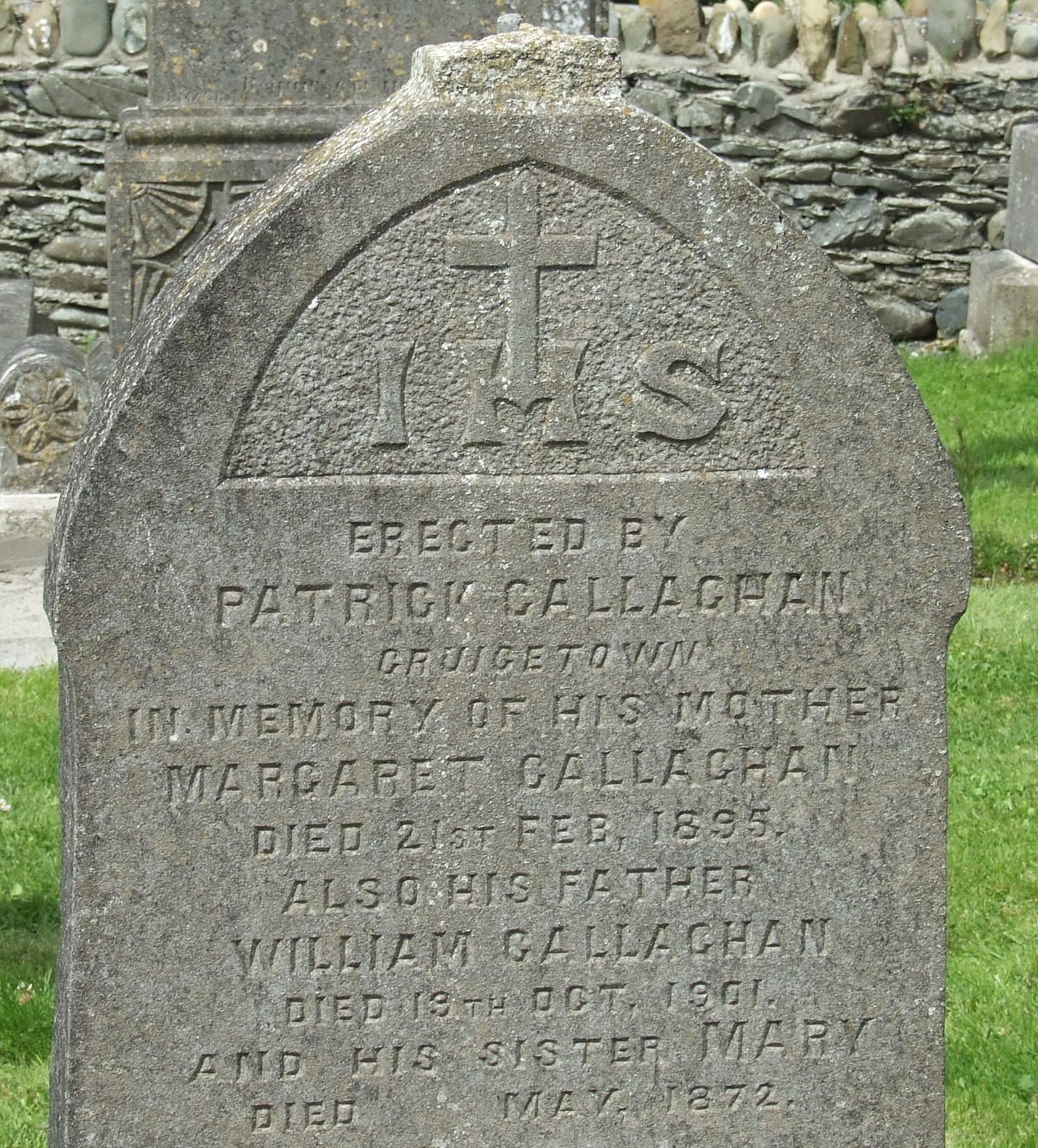

The order of commemorations on stones is not always in death date order, which may indicate relative social positions. Children who dies young are often placed after the death of the mother or both parents, and they may only give some details compared with adults. Many infants were only counted (‘also two infants’), or they may have names but no details. In contrast, some children have their ages measured down to days. Although some scholars consider that children are well represented on memorials, they are generally very under-represented when there is evidence (e.g. from burial registers) to compare with commemorations.

Some regions have a tradition where the person who arranged for the memorial is first mentioned on the inscription, sometimes in very prominent text. They may explain their relationship to the deceased and the dead are placed in the context of the living rather than the other way round.

McKerr, Lynne, Eileen Murphy, and Colm Donnelly 2009 ‘I am not dead, but do sleep here: The representation of children in early modern burial grounds in the north of Ireland.’ Childhood in the Past 2.1, 109-131. Available on academia.edu

Mytum, Harold 1994 ‘Language as symbol in churchyard monuments: The use of Welsh in nineteenth and twentieth century Pembrokeshire’, World Archaeology 26.2, 252-267.

Snell, Keith D. M. ‘Gravestones, belonging and local attachment in England 1700-2000’ Past & Present 179, 97-134.

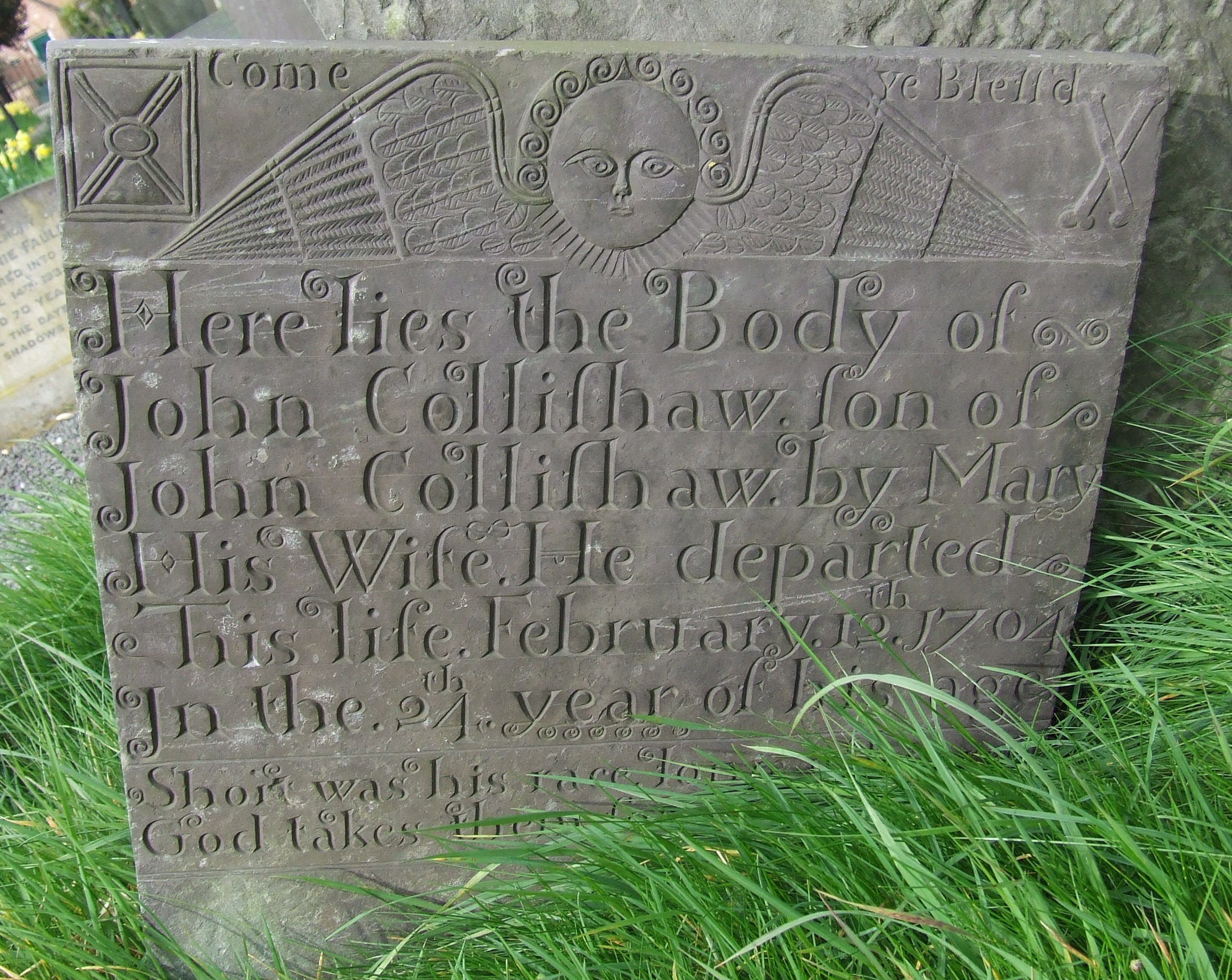

When external memorials started to be carved and placed in churchyards in significant numbers – in the very late 17th and early 18th century – they were locally carved and had distinctive characteristics. If you are fortunate to be in an area with this early start for commemoration, you can study these local styles and even identify individual carvers, though they may remain anonymous is none of their products are signed. In New England, many carvers have been identified by the style of their lettering and carving of symbols, and small number signed a few stones, but others were identified from probate records that detail the carver being paid for the memorial out of the deceased person’s estates. Sadly, this is very rare in Britain.

An early study of a regional style was by Peter Brears who identified a West Yorkshire style of carving which included a heart motif. The designs were often in false relief, but much of the text was incised. Most memorials were tomb tops or ledgers, and the style of carving is very reminiscent of wood carving. Most have a carved arch at the top with cherubs in the corners, decorated border, and the heart with initials in the centre.

Another regional style which is notable for the quality of the carving and the lettering, is that found mainly in parts of Leicester and Nottinghamshire, using the high quality Swithland slate. It had similar mix of incised and false relief lettering but was concentrated on headstones with cherub designs at the top, often with mortality symbols, though hearts also often occur. Short phrases such as ‘Momento Mori’ or ‘Be ye ready’ have negative messages, other like ‘Be ye blessed’ have a more positive one. Many of the headstones have an epitaph, and some have separate panels for different deaths.

Barley, M.W., 1948 ‘Slate headstones in Nottinghamshire,’ Thoroton Society Transactions 52, 69-86.

Brears, Peter .C.D. 1981 ‘Heart gravestones in the Calder valley,’ Folk Life 19, 84-93.

Lots of resources including the following are available for free download via https://www.hicklingnottslocalhistory.com/belvoir-angels/including:

Herbert, Albert. 1944 Swithland Slate Headstones. Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological Society 22.3: 215-240.

Lea, David 2018 Swithland Slate Headstones.

Even though many memorials start being of the designs seen across the whole country, some individual monumental masons developed their own styles, often derived from the national trends, and some of these styles became regional. You may identify both particular designs which a local mason preferred (and so, presumably, did their clients), and the regional style. A small minority of memorials have signatures of the carvers on them, and if this occurs it may be possible to put a name – and trace more information – about the workshop that produced the monuments.

An example of a local style, concentrated at Helmsley, North Yorkshire, is a distinctive form of headstone with prominent Gothic pinnacles on the shoulders the stone, and a central decorative feature based around a cross or IHS monogram in a circular ring. Ten examples reveal considerable standardisation but with small variations in every case on details of the tracery, the ring and the way in which text, if any, was inscribed round the ring. At least three memorials are signed bottom right of the inscribed in the central panel with the name BARTON. Some are eroded so the inscriptions are incomplete, but the likely date range is for deaths from 1843 to 1860. This monument form may occur elsewhere, but there is clearly a very localised concentration.

One example of a regional style is that of slate headstones made of several components that is found in North Pembrokeshire, South Ceredigion and West Carmarthenshire, with a few outliers further afield. The construction method (using wooden or metal dowels or metal straps) varies within this region, as does details of the design, showing how individual monumental masons created their own distinctive products, some of which are signed, within this tradition.

Mytum. Harold 1999 ‘Welsh cultural identity in nineteenth-century Pembrokeshire: the pedimented headstone as a graveyard monument’, in S Tarlow and S West (eds) The Familiar Past? Archaeologies of later historical Britain. London, Routledge, 215-230.

Continue on to our guidance on archiving.

Go back to the main guidance page.